Mr. Benson is Tom’s roommate in rehab. He’s about Tom’s age, and like Tom he is tall and handsome.

His eyes seem very sad. He has beautiful long eyelashes. He doesn’t smile – maybe he can’t.

Three strokes and a subsequent seizure left him without much ability to speak. When he presses the call button for a nurse, he simply says “Hello” because that’s all he can manage. People ask him to repeat things over and over, but they still don’t understand him, so he gives up.

He is a constant reminder to us of how lucky we both are. Neither Tom nor I lost our verbal ability from our strokes, though Tom has to do some speech therapy to overcome a bit of immobility around his mouth.

Today I was sitting in a chair next to Tom’s bed, reading, while he took a nap. Mr. Benson was in his wheelchair watching TV.

Suddenly a crash – Mr. Benson had fallen forward from his wheelchair and was lying in a crumpled heap in front of it.

“Mr. Benson!” I yelled. I ran to the hallway and called for help, then ran over to him and held up his head to keep it from hitting the floor.

He was struggling to right himself, but I cradled his head and told him, “You’re OK Mr. Benson, don’t try to move.” I was so afraid that he had broken bones.

I protected his head out of the instinct born of my own head trauma. The anxiety that still makes me so worried about corners and cupboards sets off a constant alarm: Protect the head! Must protect the head!

The nurses rushed in and took over. I fretted, but it seemed that Mr. Benson was OK.

We’re not sure why it happened. He says that he fell asleep, and I think that’s true. He should have been wearing the seatbelt on his wheelchair, but he might have unbuckled it.

Falls are a huge concern in caring for stroke patients. They wear wristbands that indicate the level of their fall risk.

They are often desperate to assert their independence, but they might also be disoriented, or simply impatient for assistants to show up and help them.

For the first three days in rehab, a patient’s bed has an alarm set to let the nurses know if the patient is trying to get out of bed. Once the patient proves trustworthy, they turn off the alarm.

Tom was a typical patient. In his first couple days in Cleveland, he tried to sit up and lean forward, but he fell – onto the bed, fortunately.

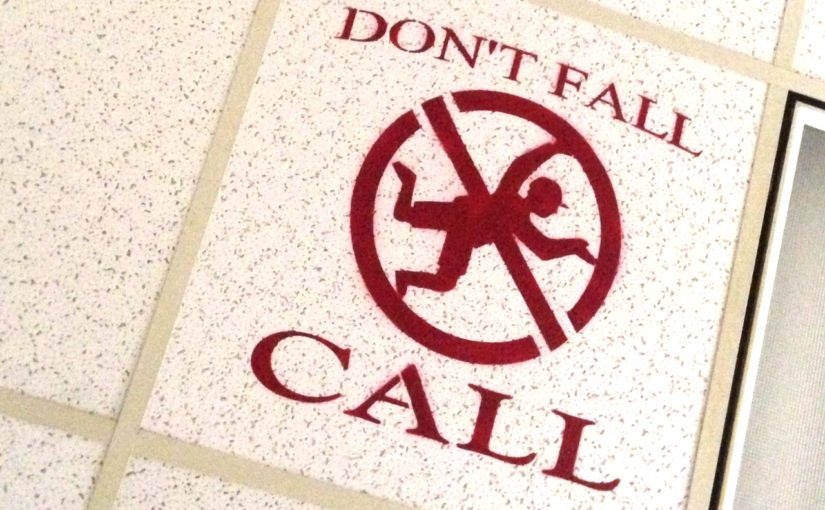

Above the bed of every patient in rehab, on the ceiling, is a sign that they see when they open their eyes.

“Don’t fall – CALL.”

For patients at risk, the most common reason they fall is that they are rushing to go to the bathroom. About 80% of falls are from that.

It’s certainly understandable. But it means the patient has to get over very ingrained potty training.

They have to consciously understand, and believe, that it is better to take a crap in the bed than to fall.

A nurse friend told me that patients over the age of 80 have to be individually evaluated for whether they should have a colonoscopy. This is because so many elderly patients fall while they are rushing to get to the toilet during the day of prep for colonoscopy, which involves completely cleaning out the large intestine.

For some patients, the risk of injury from the fall is worse than the possibility of missing early stages of colon cancer.

Mr. Benson was OK. The nurses and the resident doctor examined him carefully.

He kept saying, “I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

It was the clearest sentence I had heard him speak.

Today’s penny is a 1989. That is the year JM Morse and RM Morse published their paper on development of a scale to assess risk for fall-prone patients. The Morse Fall Scale is widely used in nursing.

How amazing that “I’m sorry” is clear….give Mr. B a hug from me.

I did. It made him cry.